Sunday Magazine, December 2009

PART I

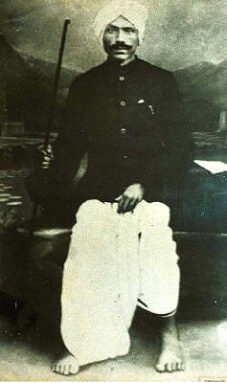

On a warm summer’s day in June 1921, a man stood by the imposing gopuram of the Parthasarathy Temple in Chennai, feeding fruit to the temple elephant. The glances of the crowd of worshippers hurrying by would rest briefly on him and move on, noticing nothing unusual except for a turban wound around his head in a manner unusual for Tamils. The man’s erect carriage was in stark contrast to signs of a certain privation; an unmistakable fragility of form, the sunken face showing up the cheekbones. Only the luminous eyes blazing out at the world showed something of the man within.

The elephant suddenly squealed and swung its trunk, hurling the figure feeding it to the ground. People ran up with cries of alarm but none dared go near the beast for fear of being trampled themselves – till a corpulent Vaisnavite Brahmin dashed up to the elephant and scooped the fallen man to safety.

The unconscious victim’s name was Subramania Bharati, and

though he recovered briefly, by September 1921 he was dead at the age of thirty nine.

Much has been written about the literary legacy of Subramania Bharati. His shadow falls everywhere upon the modern lexicon of the Tamil people. He looms over twentieth century Tamil like a titan; the man who broke with centuries of Tolkappiam tradition to create a new voice – modern and passionate – yet with a deep feeling for the past. Bharati’s songs have become perennial favourites, incorporated into that hallowed institution – the kutcheri – and sung along with the compositions of the venerated trinity of Carnatic music―Thyagaraja, Dikshitar and Shyama Sastry.

Since his voice continues to reverberate through his popular works, especially his poems and songs, the literary Bharati can be said to be reasonably alive and well―at least in the Tamil country. On his other great passions – nationalism, politics and social reform – the record is less copious, but accessible.

But it is Bharati the man that eludes us, a subject both enormously interesting and controversial to this day. He once said, “He who writes poetry is not a poet. He whose poetry has become his life, and who has made his life his poetry, it is he who is a poet.” It was the same for everything that Bharati did. He gave himself up completely to the causes and beliefs he held true, without regard to the consequences―to others and to himself. In the end, these consequences would combine to destroy him.

It is not the purpose here to dissect Bharati as a person. Amongst scholars who have devoted many years to studying his life, there seems to be a consensus that he was a man who lived in the moment: driven by an intense inner creative life that defies a conventional analysis of motive and intent. Rather, it is to throw some oblique light on this extraordinary man who is not known well enough outside his native Tamil land.

Bharati’s life can be sketched very briefly through four main punctuations. Born in 1882 in Ettayapuram in Tirunelveli district of today’s Tamil Nadu, the boy named Subramanian lost his mother at the age of two, was married when he was eleven, and when his father too died shortly thereafter, was sent alone to Benares to live with his aunt. Significantly, even in this early period in Ettayapuram, the young Subramanian displayed such facility in Tamil composition that the court of the local Raja conferred upon him the title by which he would become forever known―‘Bharati’, or one blessed by the goddess Saraswati.

Benares formed Bharati. He entered the city in 1898, a precocious but gauche village youth from the deep South who spoke only his native Tamil. By 1902, at the age of twenty, he emerged a lettered man―proficient in Sanskrit and English and with a smattering of Hindi. Then, as now, the city was a melting pot of India’s vast and diverse Hinduism. Accounts of his life there are filled with anecdotal incidents, many of them clearly life-changing. In one incident, his sensitive nature is repulsed by the sight of bulls being sacrificed at a Kali shrine when the gutters run red with blood. In another searing scene, he sees child widows tonsured and taken away to live out the rest of their lives, alone and uncared for in a widows’ home.

These and other experiences changed Bharati forever. He became convinced that Hinduism, while remaining sublime in essence, had become debased in practice. There, on the banks of the Ganges, he renounced two powerful symbols of his Brahmin identity: he cut off his tuft and threw away his sacred thread. Benares had made a radical of Bharati.

The second punctuation covers the years 1902 to 1908, when Bharati threw himself into political journalism and activism, associating himself first with the Madras-based political weekly Swadesamitran, and then with India and Bala Bharata – a magazine aimed at the youth of India. These were years when the country as a whole was awakening to its future. At Swadesamitran, Bharati had a vantage view of the undercurrents that were beginning to shake the nation, and his impetuous and fiery nature was drawn to Thilak’s call. When the Congress split between the radicals and moderates at the Surat Congress of 1907, he wholeheartedly threw his lot with the radicals and Thilak’s Revolutionary Party.

Those were heady days. In the company of close friends, he roamed Madras spreading the message of equality by advocating ‘samabandi bhojanam’ or eating together without thought to caste or creed. In the evenings, after a full day at the editorial desk, the political rallies and meetings would begin. There is a moving contemporary account of a gathering on Madras’ Marina beach by the English journalist Henry Nevinson around 1908. There, beneath a sky made red by the setting sun, a crowd of four or five thousand are gathered and against the backdrop of waves rushing upon the shore, Bharati’s voice is raised in song as he renders his immortal lines:

Vande mataram enbom―engal

manila thaiyai vanangudu menbom

(We say vande mataram, our

Respectful mother we salute)

“Through it all, there is utter peace in the gathering. There is not a policeman in sight,” writes Nevinson. Another contemporary of Bharati’s, his friend the lawyer Doraiswamy Aiyar, described the revolutionary Bharati of this time. “He was full of energy and curiosity. He spoke what he thought, directly and without dissimulation—” — clearly a trait that won him both admirers and enemies. However, ominously, “Bharati’s body was weak; his constitution frail; there were times when we felt that the smallest push would send him staggering.” Even at the age of twenty six, this was a man who lived life on the edge.

1908 was a year of stepped-up repression by the British in India. Thilak was arrested and sentenced to Mandalay prison for six years. Other associates of Bharati including VO Chidambaram Pillai, a leader of the Revolutionary Party in the south, were rounded up. Waves of other arrests followed and it was clear that Bharati’s turn was fast approaching.

Persuaded by friends, Bharati decided that his supreme task was to continue resistance through his writings for as long as possible and so slipped over the border into French Pondicherry. A new and, in many ways, dark period in Bharati’s life was commencing.

Sunday Magazine, December 2009

PART II

The revolutionaries who rallied to Thilak’s cause in the Tamil country were a curious group who deserve more attention from historians. Whilst many occupied a centrist position and (like Bharati) eschewed extremist violence, a few were convinced that radical action was the only viable option against British rule. Their machinations came to a head when a young anarchist called Vanchinathan shot and killed Robert Ash, the Collector of Tirunelveli in December 1911 at Maniyachi Junction near Madurai and then turned his gun upon himself.

Though Bharati himself was unaware of the plot and played no part in the Ash assassination, he came under inevitable suspicion as many of the conspirators were known to be close to him. The British moved swiftly to ban his publications in British India. At one stroke, Bharati’s political work was cut from beneath his feet. Simultaneously, the British set spies to keep a close tab on his movements.

It is necessary to pause here to give the reader some idea of Bharati’s personal life up to this time. Bharati never earned very much as an editor: he was also generous to a fault, often giving away what little he had in hand. He kept an open home, feeding and housing friends of all stripes and at all times, little understanding the strain this inevitably placed on his meagre resources. The result was a steady grinding poverty that was to haunt him and his family like a malign ghost all his life.

In an oft-quoted incident, Bharati comes home and finds some of their meagre store of rice carefully kept by his wife on the floor of the kitchen. Promptly, he gathers it up in his hands and begins to scatter it about the courtyard. When his wife runs up horrified, he points with delight to the birds that fly up and peck at the grain, asking her to observe them with a poet’s eye.

What then of his wife Sellammal upon whom fell the burden of managing an intense, impractical genius of a husband and her two daughters? Sellammal was married to Bharati when she was barely seven. For years she did not see him. Even when Bharati was in Madras, she was forced to live for extended periods with her parents in native Kadayam as he could simply not support a family. At the time Bharati fled to French Pondicherry, she was pregnant with their second child and the thought of having to raise her children alone up to their marriage must have been crushing.

In 1951, thirty years after Bharati’s death, she delivered a poignant talk in Tamil on the Trichy station of All India Radio on ‘Bharati – My Husband.’ “For a poet,” – she said – “words are enough for his worldly needs: he has need of nothing else. But to the very wife he describes in his poetry as ‘the queen of love’ falls the daily duty of bringing rice to the table each day to feed the stomach. What can one do with a man such as this?”

Deprived of an outlet for his political writings, Bharati turned inwards. The years of exile in Pondicherry from 1908-1918 that constituted the third main phase of his life define Bharati for posterity – when his genius burst forth in song, poetry and prose. Some of the greatest works to flow from his pen happened during the years 1911 to 1913. Whilst the posthumous Bharati is known to the public at large mainly as a poet of Indian nationalism, the fact is that the sheer breadth of his work stamps him as one of the most multi-faceted personalities of his time. His writings are outpourings that cover an astonishing array of subjects: from the sublime natural world of birds and animals (kuyil pattu or koel songs and other compositions), songs to the child (kannan pattu), love songs, devotional and philosophical compositions, besides the short story and the novel. Bharati’s mastery of the idiom of old Tamil allowed him to effortlessly sublimate it to the need for a fresh, contemporary voice, so that many of his compositions have a timeless rootedness in tradition in which a new direct, uncomplicated style and vivid imagery are overlaid to almost hypnotic effect.

Intertwined with this intensely creative life of the mind was an ever-present spectre of destitution that drove him to periodic fits of despair. In some of his most sublime compositions to his patron, the Goddess Parashakti, Bharati asks her again and again why she would treat her devotee so—when he would seek nothing more in life than to live it through her.

As if being poor was not enough, Bharati’s passion for social causes and his wilful disregard for what others thought or said of him made him a perfect lightning rod for controversy. In 1913, in one of the most debated acts of his life, he performed the sacred thread ceremony on a dalit, Kanakalingam. Joining him in the ceremony were a number of other Brahmin friends, proof – if any were needed – of the magnetic pull of Bharati on those around him.

Despite days filled with activity, some of them in the company of fellow exiles such as Sri Aurobindo Ghosh and a group of acolytes and disciples who slowly began to gather around him, it seems likely that his confinement within Pondicherry, the ever-present surveillance by British agents, gnawing poverty and also ostracism from within the orthodox sections of his own community all combined to place enormous psychological stress on Bharati. By nature he always had had a latent ascetic streak, and he now began to keep company with saamiyars – mendicants and ascetics for whom the area had long been famous. From them he took to the habit of using psychotropic substances that further weakened his already frail constitution.

Then, in November 1918, in an act of desperation, he broke exile and entered Cuddalore whereupon he was promptly arrested and lodged in Cuddalore Jail. From there he wrote a letter to Lord Pentland, the Governor of Madras. seeking his release wherein he stated:

“I once again assure your Excellency that I have renounced every form of politics and I shall ever be loyal to British Government and law abiding.”

It does not take much imagination for us to guess the inner torments that must have forced these words from Bharati’s pen. Nor did his release mean better days ahead. Constrained by lack of immediate means to live with his wife’s brother in Kadayam, Bharati had also for long been oppressed by a feeling that his works had not received the wider recognition they deserved. He wrote feverishly to many of his friends and former benefactors seeking their help in having a compendium of his life’s work published, pleading that “they will do for the Tamil Country what the works of Tagore have done for Bengal.”

Sadly these appeals did not garner the money needed for a project as ambitious as Bharati’s and this was to remain a source a bitter disappointment to him till the end. By 1919 his poems began to turn to the questions of life and death and are informed by a certain awareness of mortality. His combative nature and hot temper, however, did not seem to have cooled and a fight in Kadayam forced him to leave for Madras in 1920 where he met his death the following year.

In recent times there is a tendency amongst some scholars to aver that despite his iconoclasm Bharati never shed his Brahmin roots. There is certainly reason to believe that he resumed wearing his sacred thread (if indeed he threw it away at all in Benares), and that he gave this symbol of caste importance from the very fact that he performed the act of investing it on a dalit. Also he is said to have reacted violently to a marriage proposal for his daughter from a lower caste friend—the reason for the Kadayam quarrel. If anything, these point to Bharati’s all too human qualities, and to the difficulties of bracketing someone like him into ready categories.

In his recent introduction to ‘Deep Rivers – Selected Writings on Tamil Literature’ by Francois Gros, the Tamil scholar M Kannan writes: “Studying Tamil, one cannot escape the impression that the Tamil world generally seems to be portrayed in black and white with nothing in between and nothing beyond: Sanskrit versus Tamil, Aryan versus Dravidian, Classical versus Contemporary, Brahmin versus non-Brahmin, Tamil versus Pure Tamil, the opposing positions in which Tamil culture seems to be enmeshed are endless.”

In Bharati all these contradictions were melded together in a way that made him, quite simply, unique. In the Bharati Museum in Pondicherry is a faded photograph of his writing, a translation of a verse from the Bhakti saint Nammalwar:

Leave all

In leaving

Render your life

Unto the Master of Liberty

This December marks the one hundred and twenty seventh anniversary of Bharati’s birth. As we rush through the twenty first century, impatient in many ways with our past, we would do well to reflect in passing on this many-faceted son of India who gave so completely of himself to the liberty of his motherland.