Sunday Magazine, February 2010

In this first of a two-part series, Aroon Raman recounts the extra-ordinary story of one of medieval India’s most heroic yet little-known princes

Part I

The End of an Age

The Great Fort, Agra, August 28th 1605. Inside the gilded chambers of the Royal Quarters a man lay on his bed, dying. Senior queens of the zenana were gathered around, as were select nobles, and, slightly apart from the others, a younger man in his mid-thirties, of an obviously royal bearing. It was upon him that the gaze of the sinking man finally rested. He was not to know, even if he was in any position to reflect on it, that the prince had been smuggled into the room in the nick of time. He raised his head painfully and made a sign. A servant supported him as another reverently handed to him the robes and turban of kingship. Beckoning the prince forward, he placed them in his hands in a curiously formal yet tender gesture. Then he fell back on the cushions; his eyes roved a last time around the room and then glazed forever.

The wails of the women from the anteroom began, marking the end of one of the defining reigns in the annals of Hindustan. For almost half-a century, Jalaluddin Mohammed Akbar had been absolute master of the largest empire since Asoka. He was the greatest of the Mughals, an empire-builder of genius, whose name shines undimmed through the passage of centuries not just for what he achieved by force of arms, but for the brilliant administrative edifice through which he governed, and for the religious syncretism and tolerance that he brought to polity.

Akbar was a man far in advance of his time, but he was a man and like all men he was not perfect. So potent was his persona that none but those most gifted with talent and a strong sense of self-worth could stand up to him, and it was in his relationship with his sons that the destructive consequences of this dominance played out.

Akbar had three sons: Salim, Murad and Daniyal, born to him in 1569, 1570 and 1572 respectively. Yet, by 1605 only Salim still lived; the other two had self-destructed through addiction to opium and alcohol. At the time of his father’s death, Salim too had become over-fond of stimulants. When in the grip of arrack and opium, he was subject to violent behavior swings, capable of acts of astonishing benevolence or barbaric cruelty as the mood possessed him. Between 1600 and 1605 he had also led a series of revolts against Akbar, and war between father and son had been narrowly averted only through the interventions of Akbar’s senior begums, and by Salim’s own realization that he was militarily no match for his father.

In despair over the succession, Akbar’s mind turned to the one prince who by widespread consent had all the requisite qualities to succeed to the Mughal throne: Salim’s eldest son Khusrau. Khusrau was born in October 1567 to Salim by his first wife Man Bai, a Rajput princess from Amber. She was highly strung according to some accounts, but no trace of this showed in her son in the early years. Khusrau soon grew up to be a court favourite. Edward Terry, a clergyman at the Mughal court writes of him: “He had a pleasing presence and excellent carriage, was exceedingly beloved of the common people, their love and delight.” At 18, Khusrau was everything his father was not: personable, brave, and a talented battlefield commander.

The Struggle for Power

Inevitably, in the years just prior to Akbar’s death his court was a political cauldron, “a snake-pit of manoeuvre and intrigue” as one historian puts it, between the rival camps of Salim and Khusrau. So distressed was Man Bai at the vicious infighting that she committed suicide by taking an overdose of opium in May 1605.

By October, Akbar’s empire was poised on a knife-edge. Salim was backed by Akbar’s senior wives who wielded considerable power behind the scenes and Khusrau by the duo of Man Singh, the Raja of Amber, and Aziz Khan Koka (Khusrau’s uncle and father-in-law respectively), and others who were convinced that Khusrau was best fitted to succeed to the Mughal throne. These two were amongst the most influential nobles in the Mughal durbar and in the battle for succession, Khusrau’s star was clearly in the ascendant. That Khusrau himself was convinced of his manifest destiny as the next ruler of Hindustan is demonstrated in the way he addressed his own father as ‘Bhai’ or brother rather than as father.

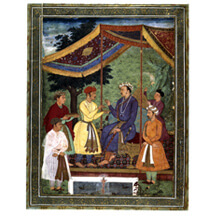

Emperor Jehangir receiving his sons Pervez and Khusrau circa 1605-06

No sooner was Akbar laid to rest than events began to move at breakneck speed. In a meeting of the senior umra called to decide the succession, Man Singh and Aziz Khan failed to persuade the majority that Khusrau was the natural choice to succeed to the crown. Akbar’s formal handing over of the robes of succession to Salim was seen by many as a clear mandate from the Emperor himself, and tipped the scales in favour of the Salim faction which carried the day. On 2nd November, 1605 Salim ascended the Mughal throne as Nurudddin Mohammed Jahangir Padshah Ghazi. One of the first acts of the new Emperor was to have Prince Khusrau confined to his quarters in the fort, with only his wife to keep him company.

Chroniclers at Jehangir’s court have understandably not been kind to Khusrau. Writing of him at this time, they record with almost dismissive disdain his descent into melancholy, some even attributing it to deficiencies in character inherited from his mother’s side. But this was a young man who had all along been offered a giddy vision of power afforded to very few; encouraged on every side including by his illustrious grandfather to believe in his manifest destiny—only to have it snatched away in the space of just hours. To anyone, the blow would have been crushing.

Crushing or not, during his confinement Khusrau’s character underwent a shift. Now that he was securely on the throne, Jehangir, to his credit, made attempts to reach out to his son, but found the prince ‘moody and distracted’. Over the next five months, the disappointment ate into Khusrau like a cancer. Goaded on by a wide network of informants and sympathizers, he made his move on April 15th , 1606. He had been given leave to visit the tomb of his grandfather Akbar at Sikandra on the outskirts of Delhi. This time he slipped past his guards and with a band of around a hundred soldiers faithful to him, rapidly made his way northwest towards Lahore.

The Rebellion

The news of Khusrau’s flight sped through the country like wildfire. Malcontents of every kind: disaffected Chugtai clans, Rajputs and some of the northern tribes flocked to his banner as did Hussain Beg, the governor of Kabul and Abdur Rahim, the Chief Minister of Lahore—both staunch Akbar loyalists. The former also threw open the gates of Rohtas Fort to the rebels and pledged the considerable treasure held there to their cause.

However, Khusrau had not foreseen the swiftness of the Mughal response. For once Jehangir acted with speed and decision. The newly appointed governor of Lahore, Dilawar Khan, raced from Agra in a forced march to Lahore in just eleven days, strengthened the defenses and sealed the gates before Khusrau’s army could reach the city. At the same time an overwhelming force of fifty thousand infantry and eight thousand cavalry was assembled at Agra at short notice and launched towards the enemy. Unable to break Lahore’s defenses, Khusrau had no option but to turn and fight.

The armies met on the north bank of the Ravi on 27th April, 1606. Fighting in heavy rain which turned the battlefield into a mud soup, Khusrau’s forces were routed within a space of six hours and he himself was captured and brought before his father in chains. Jehangir’s retribution was swift and ruthless. Hussain Beg and Abdur Rahim Khan were stripped and stuffed into the skins of a freshly slaughtered ox and ass and paraded through the streets. The skins shrank on drying and Beg was asphyxiated to death. Rahim Khan barely survived (he was later rehabilitated). Others were impaled alive on stakes by the hundreds, and Khusrau forced to ride between the screaming men to witness their agony up close. A more fateful outcome was the summary execution of the Sikh Guru Arjan Dev, whose only fault was that of blessing Khusrau on his way to Lahore, an action dictated purely by the canons of hospitality, and in no way could be construed as supporting a rebellion towards the throne. The result was a scarring of the Sikh psyche that would reverberate for centuries.

Khusrau himself was spared, but condemned to a fate almost as terrible. Either in the immediate aftermath of the rebellion or a year later, holding him complicit in a further plot against him, Jehangir ordered Khusrau blinded.

It is a measure of the popular bipartisan feeling that Khusrau was still capable of rousing that several voices at court, including those of close Jehangir loyalists, pleaded for him to be spared. But the Emperor was adamant and in one contemporary account, the act was done by wire inserted into his eyes, causing a pain ‘beyond all expression.’ He was then thrown into a dungeon. Through it all, the victim bore himself stoically, uttering not a word of remonstrance.

Thus was a much-loved prince of Hindustan cauterized from the circles of power and condemned to live out the remainder of his life in darkness and obscurity. But the saga of Khusrau was not ended. Its highest moments were yet to come, and would stand testament to the extraordinary transcendence of the human spirit.

Part II

Soon after the blinding of Khusrau, his father, possibly in a fit of remorse, ordered his physicians to see if they could restore some measure of sight to his son. With their efforts, Khusrau was spared the horror of total blindness; a thin haze of light penetrated his vision so that he lived in a shadow world where people moved as ghost images across a screen. Jehangir even began to allow Khusrau into court, to enliven his gloomy days with some purpose, but to little effect. As the monarch observed, “He showed no elevation of spirit and was always downcast and sad, so then I forbade him to see me any further ….”

Khusrau would spend the next fifteen years in confinement and under constant guard. Still, he was far from being reduced to a faceless non-entity. It is significant that whenever the Mughal Emperor travelled out of Agra, the imperial train would almost always have Khusrau in its wake, shuffling along in leg chains. Once, when Jehangir went away for four months on a hunting trip, he had Khusrau walled up in a tower, with only small holes for ventilation. This was a prince who the ruling elite still feared to leave behind alone, recognizing his hold on the popular imagination. Indeed, in an unexpected way, his reputation had grown since he had been blinded. His stoicism then and after was seen and widely commented on by observers at the time.

Khusrau also had another priceless asset: his wife. We have already seen in the previous part that he had married the daughter of Mirza Aziz Koka. In the years that followed, through all their trials and tribulations, husband and wife remained passionately devoted to each other. On being told on several occasions by Jehangir that she herself was free to do as she pleased, she consistently refused to be separated from her husband, instead tending to him lovingly, remaining by his side even when he was walled up in the tower.

The Khusrau Affair

And so the years passed for the couple. Then, in 1616 there occurred a series of events that came to be known as ‘the Khusrau affair.’ Jehangir had been now on the throne for 11 years. Apart from Khusrau, he had sired three sons: two of whom – Pervez and Shahriyar – were effete, and the warrior- prince Khurram. Khurram was a brilliant general with exceptional military and administrative gifts. In 1615, he had covered himself with glory by subjugating Mewar which had been a thorn in Mughal flesh for close to half-a-century, and his claim to succeed an ageing Jehangir seemed complete.

However, by this time the Emperor was only a figurehead. Power had since passed decisively, with his consent, to the woman who ruled in all but his name: the Empress Nur-Jahan. Since her marriage to Jehangir in 1611, she had steadily accumulated influence with all the guile of a master politician, till within a few years, it was Nur-Jahan who was the focus of power behind the throne. And in the coming of age of Prince Khurram she saw the first real threat to her dominance.

Nur-Jahan was nothing if not a consummate player in the game of power. In a bid to neutralize Khurram, she approached Khusrau for the hand of Ladli Begum, her daughter by her first husband, Sher Afghan. The adventurer Pietro Della Valle has left a fascinating account of what followed. First Nur-Jahan informed Khusrau of what he knew already, that Khurram had demanded that the custody of Khusrau be transferred to him by Jehangir. Khurram claimed that he feared another plot against Jehangir engineered by his half-brother. This fooled no one, for by now it was patently clear that Khusrau was incapable of mounting anything like a conspiracy. Khurram was simply taking steps to remove potential rivals in his path to absolute power. But Khusrau still commanded many loyalties. The same begums who had supported Jehangir against Khusrau in the early struggle for power worked hard for his safety, blocking Khurram’s demands, and as an interim compromise measure, Khusrau’s custody had been given to Nur-Jahan’s brother, Asaf Khan. Now if only Khusrau would consent to marry her daughter, Nur-Jahan promised him not only his freedom but also that she would work actively for his succession to the Mughal throne.

It was a master stroke by a master strategist—except that Khusrau refused. His reason for doing so stunned Nur-Jahan and her clique: love. His wife was his beacon, the one person who had stood by his side through all the years, and he would have nothing whatever to so with another woman. Even today, almost four centuries later, the reader might still find it hard to credit such a response. Let he or she reflect then of a time when nobles maintained harems of literally hundreds of women, where polygamy was the undisputed norm; and we can catch just a glimmer of the incredulity that must have been evoked by Khusrau’s answer. The Prince’s options were starkly laid out before him: freedom and a life of luxurious ease at the very least versus certain death. His wife, according to Della Valle, begged him on bended knee to accede to Nur-Jahan’s plan for him to marry Ladli Begum and save himself, but Khusrau “could never be prevailed with.”

The Tomb of Khusrau, Allahabad c 1870

All through 1616-17, Nur-Jahan and Asaf Khan worked on Khusrau, but he remained steadfast in his refusal to contemplate another woman. Finally they gave up and turned instead to Shahriyar, ‘who was as a puppet in their hands’. Khusrau’s usefulness to the Empress was at an end, and now she made no further effort to stall his transfer to Khurram’s custody. Khusrau had effectively signed his own death warrant. In 1617, he was given over to Shah Jahan who had him shifted to the fortress of Burhanpur in the Deccan.

By 1621, despite some interim souring of relations with his father, Khurram had, in a series of brilliant campaigns, neutralized the looming threat of Malik Amber in the Deccan, and was now again Shah Jahan—a honorific earlier bestowed upon him by a delighted Jehangir. That same year saw a counter manoeuvre by Nur-Jahan in the marriage of her daughter to Shahriyar. Being in neither camp, but seen now as a potential rival by each, Khusrau was now a man on borrowed time.

Death and Aftermath

The end came in January 1622. The most widely accepted account is that a slave of Shah Jahan’s named Raza Bahadur sought to enter Khusrau’s chambers in the middle of the night. When Khusrau refused him entry, Raza Bahadur broke open the door and rushed in with some accomplices and fell upon Khusrau. Although partially blind, Khusrau shouted out to wake his party, and then defended himself bravely, but to no avail. He was strangled and then re-arranged on his bed to make it appear as if his death was natural.

Early next day, his wife was the first to discover him. Her shrieks soon wakened the palace. On January 29th, Jehangir received word from Shah Jahan that Khusrau had died of qalanj, colic pains. But as word of Khusrau’s death swept across the empire, there was a public outpouring of grief as had not been seen for a long time. The popular verdict was overwhelmingly one of murder. As far west as Gujarat, people were heard to cry for vengeance against the man who had shed the blood of one so innocent. Jehangir himself seems to have not been unduly distressed by the news; his ire was reserved for Shah Jahan for seeking to conceal the truth of Khusrau’s death from him. On the Emperor’s orders, Khusrau’s body was exhumed from his makeshift grave at Burhanpur, transported to Allahabad and consigned in a mausoleum next to his mother’s in a garden—now called Khusrau Bagh. For a while a movement came into being that proclaimed Khusrau a martyred saint and shrines sprang up in all the places where his body had rested on the way to Allahabad. So popular were these shrines that according to a contemporary Dutch observer ‘both Hindus and Moslems went there in vast numbers in procession each Thursday…to his worship.’ Until, that is, Jehangir ordered them destroyed and the worshippers driven away.

Despite these attempts at canonization, it seems fair to say that as in life, death has not been much kinder to this unfortunate prince. In one of the great ironies of history, the man who most likely killed him – Shah Jahan – is universally celebrated for leaving us with that sublime monument to man’s love for a woman: the Taj Mahal. Devoted as he was to his wife Mumtaz Mahal, Shah Jahan in fact had liaisons with many women after her death. Rather, it is in the unfolding of his brother’s life, in Khusrau’s searing affirmation of the centrality of one love, that we see its most enduring monument.