Published by The Hindu, November 6, 2010

The sky is red in clouds, and from the terrace of the Lake Palace Hotel the eastern shore of Lake Pichola presents a fantastical panorama straight out of the pages of the Arabian Nights. Udaipur is never more compelling than at sunset; the undulating mosaic of whitewashed squares, brick facades and chatris from an older age are all lit by a russet glow of the dying sun. The immense medieval pile that is the City Palace dominates the shoreline, where the lake is a shifting mirror: blue, red ochre and silver all at once as it reflects the city against the backdrop of the Aravalli Hills. That indefatigable chronicler of Rajputana, Colonel James Tod, once described Udaipur as the ‘most romantic spot on the continent of India’ and 150 years later, it is still easy to see why.

As I sip my drink, my eyes are drawn to the hills. They appear somehow primordial in the deepening dusk, and suddenly I am reminded that the Aravallis are described by geologists as amongst the oldest mountains on the planet. But beyond their geological significance, these ranges have defined this extraordinary land of Mewar as few mountain tracts in history.

Mewar. The very name now has a martial ring to it: a call to arms, of death before dishonour, of a ferocious resistance against overwhelming odds. From the time of its founding by Bappa Rawal, the names of Padmini of Chitor, and the Sisodia Ranas – Kumbha, Sangram Singh and the great Pratap – even today live enshrined in the memories of millions. But if the annals of its blood-soaked past are filled with heroism, so too are they a testament to internecine warfare, of patricide, of a mindset rooted in ancient codes of warfare that time and again were to prove fatal against the modernism of the invader.

Nowhere was this so decisively demonstrated as in the Battle of Khanua in March 1527. The Rajputs, coming together for one of the few times in their history, fought with desperate courage, but their valour was no match for the artillery and matchlocks that Babur used to devastating effect. Many historians aver that this was the battle that truly laid the foundation of the Mughal Empire in India. The leader of the Rajput confederacy, Rana Sangram Singh (Sanga), barely managed to escape, only to die the following year.

For the next 13 years, Mewar descended into a long night[Passive tense]. In 1534, Bahadur Shah of Gujarat took advantage of the feckless reign of Sanga’s son Vikramaditya and laid siege to Chitor. Vikramaditya fled the fort, leaving its defence to his generals. The infant son of Rana Sanga, Uday – the last of the Mewar line – was also sent into hiding. Though Chitor was saved by Mughal forces under Humayun (who happened to be a rakhi brother to the queen), the groundswell of hatred for Vikramaditya’s callow cowardice caused his nobles to depose him, and Banbir, an illegitimate son of Sanga, was placed in executive authority. Banbir’s remit was to serve as regent till the young Uday Singh came of age, but he soon developed other plans: sole, supreme power.

Now opens an episode in the annals of Mewar that has few parallels for its heroism, a starburst of such brilliance that even today it lights up the pages of Mewar’s chequered history. We have seen earlier that when all seemed lost, Uday Singh had been spirited away to Bundi in the keeping of his wet nurse or dai, called Panna, a woman from Pandoli in the service of Rana Sanga.

One night, when she was putting Uday to sleep, Panna heard screams in the adjoining wing of the palace seraglio. Soon after, the family barber rushed into the room. Banbir, he told Panna Dai, had just assassinated Vikramaditya and was on his way to kill the child. They had only moments. Panna snatched up the prince and placed him in a fruit basket. Covering it with leaves, she handed the pannier to the barber, all the while whispering instructions to him. Then she moved to the corner of the room where lay her own child, Chandan. She quickly placed Chandan on Uday’s cot and had barely settled herself down when Banbir burst into the room.

Close to five centuries after, the scene still rises in macabre detail before the mind’s eye. The lamp-lit chamber, the maidservant huddled by the bed, and the half-crazed Banbir holding a blood-stained blade. He throws a malevolent look at this frail, insignificant-looking woman and then speaks a single, grating question. Panna cannot trust herself to reply; she points a trembling finger at the infant sleeping in the royal cradle. Banbir lunges towards it; Panna shrieks once and swoons. When she comes to, it is to the sight of her slaughtered Chandan, the child she not long before had fed from her breast before putting him to sleep. But, even through her grief, she knows what she must do.

Photo Courtesy: Maharana of Mewar Charitable Foundation

Having, in the words of Tod, “consecrated with her tears the ashes of her child”, Panna made her way to the bed of the Beris River, a few miles west of Chitor. Here the barber awaited her with his precious charge. Taking the still sleeping boy into her arms, she began what would be the first of her many journeys through the perilous wilderness of the Aravallis.

The name Panna means diamond. Never was a name more aptly given. Over the next weeks and months, this seeming wisp of a woman would single-handedly protect her charge against impossible odds. Her first destination was Deolia, to place Uday in the protection of the chieftain, Rawat Rai Singh. Finding the latter reluctant to accept them on account of his fear of Banbir, she proceeded to Dungarpur, where her plea for sanctuary was again turned down. With the risks of discovery and betrayal ever-present, Panna began her most desperate journey, on a circuitous tract that wound through the Mewar Hills into the very heart of the maze of valleys and jungles that form the southern spur of the Aravallis.

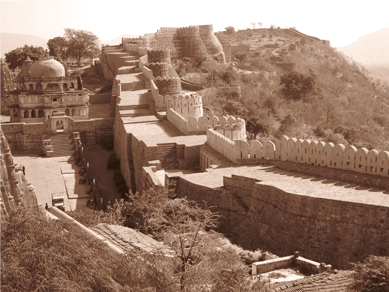

Kumbhalgarh in the Aravallis (photo: Aroon Raman)

Despite the encroachment of modern civilization with its roads and resorts into the Aravallis, a traveller in these parts today will still be struck by the immensity of its wilderness. Looking at a map of Rajasthan in 1595 as drawn by Prof. Irfan Habib in his seminal Atlas of Mughal India, one can see the words ‘dense forest’ written over this area, bereft of all human settlement. Tigers, bears, cheetahs and leopards roamed the forests in teeming numbers. It is certain that Panna would never have made it through alive but for the help she received from Bhil tribals, to whom this forest country was home from time immemorial.

At last, exhausted and near despair, she reached the great mountain fastness of Kumbhalgarh. There “she demanded an interview [with the governor Asa Shah]…which being granted, she placed the infant in his lap and bade him ‘guard the life of his sovereign’”. Asa initially hesitated, but he was a Jain, and when his mother exhorted him to do his duty, he took the child in. Panna then withdrew from Kumbhalgarh to draw away suspicion from Uday, who was, for a while at least, to be brought up as Asa Shah’s son.

The years passed and it became common knowledge that the true prince of Mewar had risen again in Kumbhalgarh. The sardars of Mewar gathered to declare him king, and soon their combined armies deposed Banbir and sent him into exile. Rana Uday Singh ascended the throne of Mewar in 1541 AD.

The reader who has followed our story thus far is surely justified in expecting a fairytale ending. Unfortunately, the reign of Uday Singh was undistinguished and [Even if he accomplished nothing significant in his lifetime, you need to say that his being on the throne ensured that his line continued unbroken. The following sentence is an anticlimax after the drama of what precedes, and reduces Panna’s sacrifice. We need to be told about its success.]Mewar was to endure another sack of Chitor, this time by the great Mughal emperor Akbar.

Still, Panna Dai’s supreme courage and self-sacrifice did not go in vain. She continued to serve Uday Singh’s family till the end of her days, living long enough to see the line of Bappa Rawal survive in the person of Uday’s eldest son, Pratap. Rana Pratap Singh would, for 25 long years, hold aloft the banner of fierce independence against the greatest army in the known world of the day and restore to Mewar much of her lustre. Panna’s legacy lives on in another respect too: Uday Singh went on to found the city that still bears his name—Udaipur.

From the deck below I can hear the strains of a sitar mingling with the voices and laughter of other guests. High above, the saptarishi constellation hangs like a diadem in the heavens. The water is lit softly by the lights of the hotel, and across the lake, by the effulgence of the City Palace. The Aravallis have been blacked out by darkness, but as I stare out into the night, I see her in every detail: a lone woman clutching the young body close and making her slow way into the hills.

Note: The author is grateful to the Maharana of Mewar Charitable Foundation (MMCF) for assistance with some facts for this article. Since 1997, MMCF has instituted the Panna Dhai Award for sacrifice above and beyond the call of duty.